Chapter Four of Dilexit Nos

This is the fifth in a series of reflections by Nathaniel Marx on the final encyclical letter of Pope Francis, Dilexit Nos.

Come to the Water

Hydration is the first concern of athletes and camp counselors as the weather heats up. This is the time of year when I begin each day filling water bottles to send with my kids before delivering them to various summer activities. “Hydrate, don’t die-drate!” is their favorite admonition to siblings and friends. Few things are less fun than finding your canteen dry halfway through a sweltering run, ride, or hike. If you try to set speed records and skip water breaks, you might not reach your destination at all.

Chapter four of Dilexit Nos requires a measured pace, lest it become a slog. It is the longest chapter by far, but its chronological organization offers several resting places where a reader might pause and feel refreshed, not inundated, by Pope Francis’s words.

- DN 92–101: The Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament

- DN 102–108: From the Martyrs to Bonaventure

- DN 109–113: Medieval Mystics

- DN 114–128: Francis de Sales, Mary Margaret Alacoque, and Claude de la Colombière

- DN 129–142: Charles de Foucauld and Thérèse of Lisieux

- DN 143–147: Jesuit Spirituality

- DN 148–150: Recent Saints

- DN 151–163: The Devotion of Consolation

Have a drinking glass handy, anyway, since chapter four’s main image is flowing, thirst-quenching water. Beginning with the prophets of Israel, Francis describes God’s promise of life-giving water and its fulfillment “in the pierced side of Christ, the wellspring of new life” (DN 96). Wherever streams of mercy and grace appear in Christian spirituality over the centuries, saints of every era and vocation trace that living water to its source in the wounded heart of Jesus.

Flowing from His Heart

Chapter four contains the encyclical’s most direct references to the sacraments. Traditionally, the blood and water that flow from Jesus’s pierced side signify not only Eucharist and baptism, but the church that receives and confers Christ’s life through all his sacraments (cf. Jn 19:34). Pope Francis highlights the strands of this tradition that link sacraments and intimate friendship with Jesus. Thus, liturgy and contemplation flow together to form “a broad current” (DN 148), uniting public and personal prayer, and harmonizing exterior and interior worship.

Francis especially credits the Franciscan theologian St. Bonaventure with uniting the “two spiritual currents” of sacraments and friendship (DN 106). According to Bonaventure, the grace that flows from “‘the hidden wellspring of his heart’” enables the sacraments “‘to be, for those who live in Christ, like a cup filled from the living fount springing up to life eternal’” (DN 107).

Bonaventure then asks us to take another step, in order that our access to grace not be seen as a kind of magic or neo-platonic emanation, but rather as a direct relationship with Christ, a dwelling in his heart, so that whoever drinks from that source becomes a friend of Christ, a loving heart. “Rise up, then, O soul who are a friend of Christ, and be the dove that nests in the cleft in the rock; be the sparrow that finds a home and constantly watches over it; be the turtledove that hides the offspring of its chaste love in that most holy cleft.” (DN 108)1

In the remainder of the chapter—indeed, throughout the entire encyclical—the association of the pierced side of Jesus with his heart proves crucial to identifying the saving power of Christ’s sacrifice with his human and divine love. This perennial insight and experience of the saints keeps liturgy from becoming theurgy and contemplation from becoming esotericism.

“Renewed in the Love of God”

Along with the image of living water, the consistent theme linking the diverse saints cited in chapter four is renewal. Those devoted to the heart of Jesus include monastic reformers like Bernard of Clairvaux, William of Saint-Thierry, and Ludolph of Saxony. They include reformers from the mendicant orders, like Catherine of Siena, founders of new congregations, like John Eudes, and nurturers of lay spirituality, like Francis de Sales. Also influential are the women mystics who “have spoken of resting in the heart of the Lord as the source of life and interior peace.” St. Gertrude of Helfta explains the refreshment available even now to those who recline their heads on the heart of Christ. “‘The sweet sound of those heartbeats has been reserved for modern times, so that, hearing them, our aging and lukewarm world may be renewed in the love of God’” (DN 110).

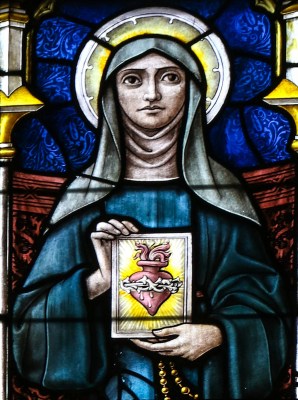

Of course, “modern times” for Gertrude the Great meant the thirteenth century. Devotion to the Sacred Heart as we know it took its modern form from St. Margaret Mary Alacoque. Dilexit Nos commemorates the 350th anniversary of the apparitions of Christ that St. Margaret Mary received between December 1673 and June 1675 (DN 119). This “new declaration of love” inspired the widely copied painting by Pompeo Batoni that hangs in Rome’s Church of the Gesù. The “core of the message” that Christ handed on through St. Margaret Mary may be summed up, Francis says, in the words she heard. “‘This is the heart that so loved human beings that it has spared nothing, even to emptying and consuming itself in order to show them its love’” (DN 121).2

Consoled as to Console

If the revelations to St. Margaret Mary renewed love for the heart of Jesus, Dilexit Nos proposes a particular renewal of two practices that accompany modern devotion to the Sacred Heart. Reparation to the heart of Christ is discussed in chapter five. Here in chapter four, Francis considers the contemporary value of the devotion of consolation. This is the contemplative prayer that “allows us to be mystically present at the moment of our redemption” and console Christ in the sufferings of his Passion (DN 152).

“It might appear to some that this aspect of devotion to the Sacred Heart lacks a firm theological basis,” Francis admits. But the faithful know better how remembrance (anamnesis) works not only to inform faith but, through faith, to unite us with the one we remember.

Here the sensus fidelium perceives something mysterious, beyond our human logic, and realizes that the passion of Christ is not merely an event of the past, but one in which we can share through faith. Meditation on Christ’s self-offering on the cross involves, for Christian piety, something much more than mere remembrance. This conviction has a solid theological grounding. We can also add the recognition of our own sins, which Jesus took upon his bruised shoulders, and our inadequacy in the face of that timeless love, which is always infinitely greater. (DN 154)

The question today is what sense the faithful make of the “desire to console Christ, which begins with our sorrow in contemplating what he endured for us” (DN 158). Is there not a potential misunderstanding of responsibility and atonement here that would leave us feeling like the perpetrators of Christ’s Passion rather than its beneficiaries? The pope does not back away from scriptural claims that “believers who fail to live in accordance with their faith ‘are crucifying again the Son of God’” (DN 156; cf. Heb 6:6). But Francis emphasizes “the unity of the paschal mystery.” Those who try to live in accordance with their faith find that “the risen Lord, by the working of his grace, mysteriously unites us to his passion” (DN 157). Then, we experience “compunction” not as lingering guilt, but as “a beneficial ‘piercing’ that purifies and heals the heart” (DN 159).

The devotion of consolation might nevertheless appear to justify or even glorify suffering caused by illness, misfortune, or the sins of others. “Whenever we offer some suffering of our own to Christ for his consolation,” Francis assures us, “that suffering is illuminated and transfigured in the paschal light of his love” (DN 157). By accepting our sufferings offered in consolation, Christ does not give us a reason or rationale for undeserved suffering. Instead, he gives us his heart.

If we believe that grace can bridge every distance, this means that Christ by his sufferings united himself to the sufferings of his disciples in every time and place. In this way, whenever we endure suffering, we can also experience the interior consolation of knowing that Christ suffers with us. In seeking to console him, we will find ourselves consoled. (DN 161)

The love that suffers with us gives itself as drink that satisfies our thirst and makes us wellsprings of consolation in turn. “As Saint Paul tells us, God offers us consolation ‘so that we may be able to console those who are in any affliction, with the consolation by which we ourselves are consoled by God’” (DN 162; cf. 2 Cor 1:4).

Please leave a reply.