By JP Misheff, November 12, 2025

The 2025 National Study of Catholic Priests reveals a priesthood in transition — marked not only by generational divides, but by deepening questions of trust, leadership, and pastoral identity.

Drawing on longitudinal data from thousands of priests across the U.S., the study highlights shifts in well-being, theological orientation, and views on Church governance. While younger priests continue to trend more theologically “conservative/orthodox,” the report also surfaces widespread concerns about burnout, evolving pastoral priorities, and the complex relationship between clergy and bishops in a post-crisis Church.

The study, conducted by Gallup, examines generational trends by categorizing priests according to their ordination periods: before 1980, between 1980-1999, after 2000, and post-2010. One of the most glaring trends is the clear shift away from “liberal” self-identification. Of priests ordained prior to 1975, 61% identified as “very” or “somewhat” liberal, with around 13% conservative. Of those ordained since 2010, 37% self-identify as politically moderate, with 51% landing in the “very” or “somewhat” conservative group. Around 1 in 10 of younger priests consider themselves liberal. Those ordained between 2000-2009 hold the largest share of moderates.

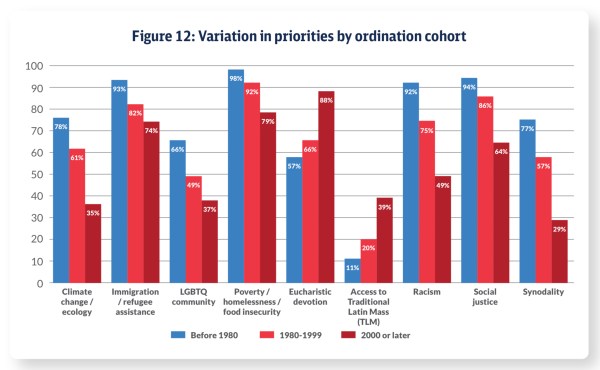

The study shows further evidence of this divide in the shifting views on Eucharistic adoration and synodality. Adoration is still a high priority for 57% of those ordained before 1980, but for those ordained after 2000 it soars to 88%. And where 77% of those ordained before 1980 hold synodality in high regard, only 29% of the post-2000 group see it that way. Another stark difference is in favorability to the Latin Mass. Only 11% of priests ordained before 1980 said access to the TLM should be a priority, compared with 20% from those ordained 1980-1999, and from 2000 on the number nearly doubles to 39%.

Highlighting an even sharper dichotomy is the area of theological view: 70% of priests ordained before 1975 are theologically “progressive,” whereas 70% of priests ordained after 2000 describe themselves as “conservative/ or orthodox” -only 8% of the younger cohort identified as “progressive.”

The survey also shows what many have perceived or heard directly from clergy: burnout and loneliness is on the rise with younger priests, with religious priests feeling the burn more than their diocesan counterparts, by 69% to 56% respectively.

The top areas of agreement among the entire cohort (94%) are around the shared priorities of youth and young adult ministry, family formation/marriage prep, and evangelization.

The results of this study show younger clergy mirroring similar secular trends: frustration with and subsequent movements away from long-prevailing Baby Boomer-era sensibilities. Recent sociological studies and commentaries reveal this generational trend.

Younger Gen X and elder Millennials had already kicked off the so-called slow movement — a reaction to the fast and furious pace of our culture, especially after the 1980’s.

More recent research shows Gen Z and Millennials expressing skepticism toward institutions skewing liberal, and politics in general, while increasingly embracing slower, more traditional lifestyles, seeking stability in a rapidly changing and increasingly polarized world.

Gen Z especially is getting married earlier, partying less and has expanded the definition and range of slow lifestyles. Social media trends show a rejection of hookup culture and a rise in traditionalist, domestic hobbies like baking, gardening, and crafting.

The above trends are the findings of the youngest members of Gen Z, following on the tail of only slightly earlier trends which showed Millennials, the older grandchildren of Baby Boomers, skewing much more progressive, rejecting religion, marriage and having children altogether. These clearly opposing trends, occurring in tandem, in successive generations, reveal some of the tensions wrought out of this broader transitory period currently under way.

Traditional longings have resonance for the spiritual life, particularly around devotions and frequenting the sacraments. Here at Saint John’s University, the monks of the Abbey have responded to the increasing number of students asking for opportunities to participate in communal prayer and sacraments apart from daily Mass.

The response has been warm and affirmative. This year alone sees a significant increase of more “traditional” devotional and sacramental offerings from the Abbey. Confession opportunities have nearly tripled for the community at large, and another weekly adoration service has been added. On Thursday nights in Emmaus Chapel, home of the School of Theology and Seminary, 20-40 students regularly attend Eucharistic adoration, hosted by SJU Faith. In addition, Sunday evenings in the Abbey Church are devoted to Eucharistic Adoration and Benediction, replete with music and an extended period of silence.

Opinion/Response

For this writer, of particular note is this fleeting group of moderates in the 2025 study mentioned above. A small window of priests ordained between 2000-2009 held on to a “middle ground.” But on either side of that window, one sees opposing views moving off in either direction. Is this yet another case of the pendulum continuing its eternal back-and-forth swing, fueled by each successive generation’s reaction to the one before it?

Another question arises: Is there a stable, sustainable middle ground upon which we could peacefully coexist? What would it take for such a space to hold? Does it require sacrifice? From whom? Are not everyone, on all “sides” invited to surrender something? At what time and in what way? What would such a sacrifice look like on an individual and collective level?

Reform is good, and yes, necessary at times. But how we respond, how we engage in it, is everything.

To borrow from Benedictine terms, what might the introduction or maintenance of a practice of statio look like? Before we instigate any change whatsoever, both individually or corporately, before we proceed with any shift of any degree, there is an invitation to stand still, in statio, a holy pause. This is a time we can willingly, reverently enter into, a time to subject ourselves to a space of sober reflection and open-minded observation, for centering ourselves humbly in God. How am I positioned? Am I being called to move? Here we may discover that we revolve around Him, that He is our pivot point. Not the other way around, wherein we find ourselves perennially faced with those two basic, human-crafted options: left or right, red or blue, etc.

The monks of Saint John’s Abbey have recently embarked on a 5-year-long prayerful period of reflection, a prolonged statio one might call it, as they discern a way forward with their liturgical proceedings. Much care has been taken to avoid politics-as-usual. The group has proceeded together, on relatively equal footing, with every voice and perspective heard and incorporated. Of course, these are humans we’re talking about so one imagines that the process has had its inevitable share of hiccups. But now we see a community facing together a future formed in union — in alignment, they pray, with God’s plan for their shared space.

Here we are seeing what a slow, reflective approach toward religious and theological progress, rooted in tradition, might look like. Here, it looks like the addition of Eucharistic Adoration in the Abbey Church, a bastion of post-Vatican II reform. One doesn’t need to squint to see the monk community radically responding not just to the times, but to a holy longing both from within and outside the community.

Here’s to more holy pauses, more measured time of collective reflection between seismic cultural/political/religious shifts. On a personal level, here’s to a prayerful, lingering silence between the last sip of our morning coffee and getting up to conquer the day. Here’s to carving out more spaciousness in our individual lives, more intentional, sober responses to the infinite variables flying at us at any given moment. And here’s to recalling humbly that we revolve around Christ, knowing that it’s so much better when we do it together.

We know you must have some thoughts on this. We’d love to hear them. The writer of this article will be paying close attention to incoming comments, feedback, criticism. Please do consider commenting below. We’ve intentionally made it easier for visitors to comment. While we encourage a broad range of perspectives, we do ask you to engage peacefully.

Please leave a reply.