Category: Teaching Liturgy

-

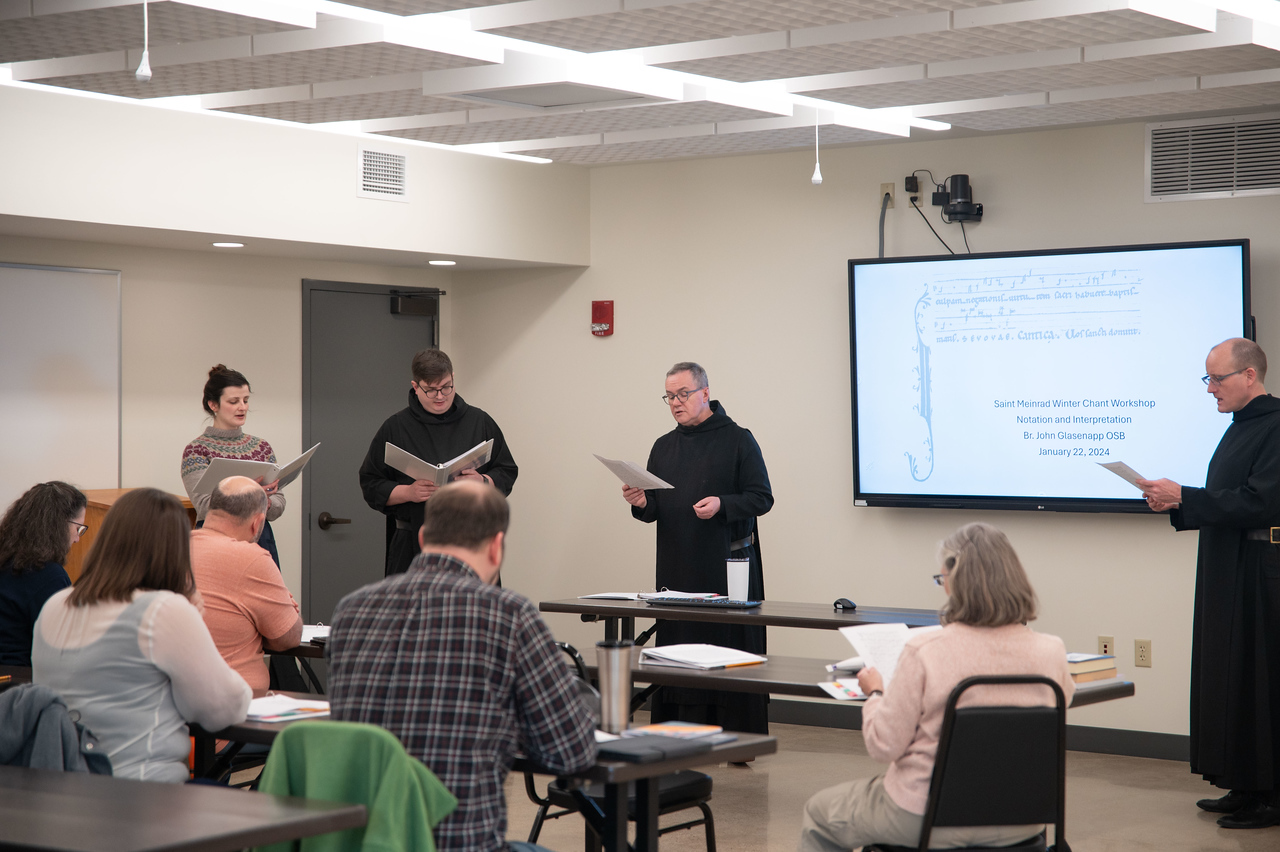

The Saint Meinrad Institute for Sacred Music: An Interview with Br. John Glasenapp, OSB

JEANA VISEL, OSB — At Saint Meinrad Seminary and School of Theology in southern Indiana, a new Institute for Sacred Music has recently launched.

-

Brief Book Review: Historical Foundations of Worship

A common basis for the study of liturgical history that can be appreciated by readers of any Christian tradition.

-

Brief Book Review: Guide for Forming a Parish Bereavement Ministry

A concrete example of how to do liturgical/sacramental theology with the Church’s rites as a starting point, and how to incarnate that theology in the spiritual life of the parish and its members.

-

Amen Corner: A Different Checklist

As preparations for the Paschal Triduum intenstify, Genevieve Glen, OSB, reminds us of liturgy’s ultimate goals in this quarter’s Amen Corner.

-

The North American Academy of Liturgy, 2023

A joyful reunion to give papers, socialize, catch up with news personal and academic, and sit together as an academic community…

-

For the Season of the Word: A Biography of the Lectionary

“A treasure trove of insights which flow from the author’s work on this book…an important and exemplary…partner in formation with the Lectionary and the liturgical year.”

-

Brief Book Review: Theological Foundations of Worship

This collection represents scholarship from a variety of denominations and “churchmanships” and shows the remarkable points of convergence in the theologies of liturgy.

-

Amen Corner: The Fijian Meal Tradition

Could aspects of Fijian cultural meals be incorporated into the church’s eucharistic tradition?

-

One Flock, Walking Together

“When I join a communion procession, do I engage in this action as though I were a customer in line at a supermarket or an amusement park?”